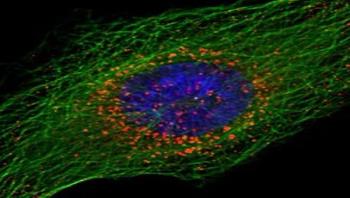

Even if they appear clean, your hands can be a vehicle for spreading potentially deadly foodborne illnesses and healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). To reduce the transmission of pathogens, proper and regular hand care is key. Equally important is creating accountability around hand hygiene among employees. But are we focusing too much of the discussion on which pathogens are killed and in how many seconds? Are these facts convincing employees to increase handwashing and the use of hand sanitizer at critical moments? Unfortunately, the current approach isn’t as effective as it could be. And without compliance, these disease-causing microorganisms remain on hands. Uncovering factors that increase compliance can help protect employees, building visitors and an organization’s brand.