News

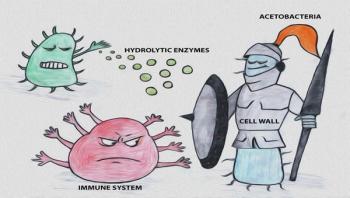

Researchers at Umeå University in Sweden have published new findings on the adaptation of the bacterial cell wall in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. The study reveals novel bacterial defense mechanisms against the immune system and how they can become resistant to antibiotics.

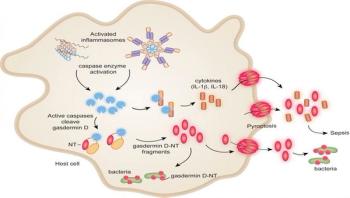

Bacterial infections that don't respond to antibiotics are of rising concern, as is sepsis -- the immune system's last-ditch, failed attack on infection that ends up being lethal itself. Reporting online in Nature on July 7, researchers at Boston Children's Hospital describe new potential avenues for controlling both sepsis and the runaway bacterial infections that provoke it.

A collaborative Michigan State University study involving microbiologists, epidemiologists, animal scientists, veterinarians, graduate students, undergraduates and farmers could lead to better prevention practices to limit dangerous E. coli bacteria transmissions.

University of Pennsylvania engineers have developed a rapid, low-cost genetic test for the Zika virus. The $2 testing device, about the size of a soda can, does not require electricity or technical expertise to use. A patient would simply provide a saliva sample. Color-changing dye turns blue when the genetic assay detects the presence of the virus.

A study that is first in its kind and published in Nature Medicine today has looked at how far genetic factors control the immune cell response to pathogens in healthy individuals. A team investigated the response of immune cells from 200 healthy volunteers when stimulated with a comprehensive list of pathogens ex vivo (outside the human body), and has correlated these responses with 4 million genetic variants (SNPs). The study was performed by scientists from University Medical Centre Groningen, Radboud University Medical Centre (both in the Netherlands) and Harvard Medical School. The paper was published July 4, 2016.

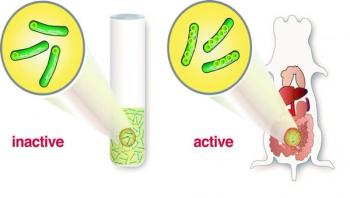

Researchers at Umeå University in Sweden are first to discover that bacteria can multiply disease-inducing genes which are needed to rapidly cause infection. The results were published in Science on June 30, 2016.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have confirmed that a benign bacterium called Wolbachia pipientis can completely block transmission of Zika virus in Aedes aegypti, the mosquito species responsible for passing the virus to humans.

Most people recoil at the thought of ingesting E. coli. But what if the headline-grabbing bacteria could be used to fight disease? Researchers experimenting with harmless strains of E. coli -- yes, the majority of E. coli are safe and important to healthy human digestion -- are working toward that goal. Specifically, they have developed an E. coli-based transport capsule designed to help next-generation vaccines do a more efficient and effective job than today's immunizations.

Tuberculosis is one of the most common infectious diseases in the world, infecting almost 10 million people each year. Treating the disease can be challenging and requires a combination of multiple antibiotics delivered over several months. This is due, in part, to variations in antibiotic tolerance among subpopulations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacteria that cause tuberculosis.