News

Reprocessing endoscopes, particularly flexible endoscopes, requires numerous steps for proper cleaning and high-level disinfection. Studies have demonstrated that not all of these steps are followed by sterile processing personnel, leading to potential transmission of infectious organisms to patients during invasive procedures using contaminated scopes.

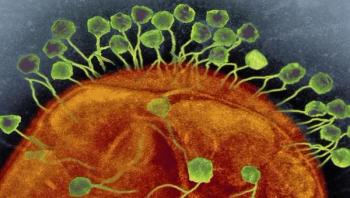

Scientists and physicians at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, working with colleagues at the U.S. Navy Medical Research Center - Biological Defense Research Directorate (NMRC-BDRD), Texas A&M University, a San Diego-based biotech and elsewhere, have successfully used an experimental therapy involving bacteriophages -- viruses that target and consume specific strains of bacteria -- to treat a patient near death from a multidrug-resistant bacterium.

This year's state of the industry report on sterile processing, with data provided through an online survey of ICT readers who work in sterile processing departments (SPDs) and central sterile supply departments (CSSDs), is designed to offer a snapshot of the key issues and challenges relating to budgets, resourcing and workloads, as well as human factor-related issues.

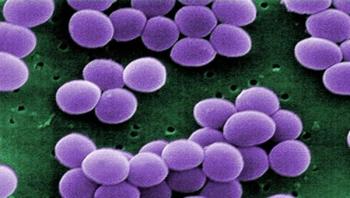

The quest to make a hospital an infection-free environment seems never-ending. That’s especially the case as new antibiotic-resistant bugs crop up and as staph and sepsis continue to risk patient lives. The responsibility for addressing these problems does not rest solely on infection preventionists, of course, but there are measures these healthcare professionals can and should implement to better ensure a highly functioning safety of culture.

Scientists have built a large body of knowledge about Lyme disease over the past 40 years, yet controversies remain and the number of cases continues to rise. In the United States, reported cases of Lyme disease, which is transmitted from wild animals to humans by tick bites, have tripled in the past 20 years. A multitude of interacting factors are driving the increase in Lyme disease cases, but their relative importance remains unclear, according to Marm Kilpatrick, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz. Nevertheless, he noted that there are a number of promising strategies for controlling the disease that have not been widely implemented. Kilpatrick is lead author of a paper published April 24 in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B that examines the complex array of factors influencing the prevalence of Lyme disease and identifies the major gaps in understanding that must be filled to control this important disease.

When the standard malaria medications failed to help 18 critically ill patients, the attending physician in a Congo clinic acted under the "compassionate use" doctrine and prescribed a not-yet-approved malaria therapy made only from the dried leaves of the Artemisia annua plant. In just five days, all 18 people fully recovered. This small but stunningly successful trial offers hope to address the growing problem of drug-resistant malaria.

A study from Indiana University has found evidence that extremely small changes in how atoms move in bacterial proteins can play a big role in how these microorganisms function and evolve. The research, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is a major departure from prevailing views about the evolution of new functions in organisms, which regarded a protein's shape, or "structure," as the most important factor in controlling its activity.