News

With nearly 3.2 billion people currently at risk of contracting malaria, scientists from the Institut Pasteur, the CNRS and Inserm have experimentally developed a live, genetically attenuated vaccine for Plasmodium, the parasite responsible for the disease. By identifying and deleting one of the parasite's genes, the scientists enabled it to induce an effective, long-lasting immune response in a mouse model. These findings were published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine on July 18, 2016.

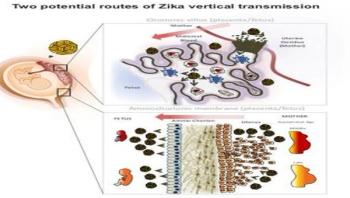

Zika virus can infect numerous cell types in the human placenta and amniotic sac, according to researchers at UC San Francisco and UC Berkeley who show in a new paper how the virus travels from a pregnant woman to her fetus. They also identify a drug that may be able to block it.

Colorado State University researchers led by Olve Peersen, a professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, have designed a genetic modification to one type of coxsackievirus that strips its ability to replicate, mutate and cause illness. They hope their work could lead to a vaccine for this and other viruses like it.

In a 2006 lecture, "Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases: The Perpetual Challenge,' Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), alluded to a statement made by physician and anthropologist T. Aidan Cockburn in 1963 in a book titled The Evolution and Eradication of Infectious Diseases. Cockburn declared, "We can look forward with confidence to a considerable degree of freedom from infectious diseases at a time not too far in the future. Indeed, it seems reasonable to anticipate that within some measurable time … all the major infections will have disappeared." In the midst of the Zika outbreak and having recently experienced the Ebola pandemic and less recently the MERS, H1N1 influenza and SARS outbreaks, and seeing infectious diseases such as poliovirus re-emerge, Cockburn's declaration from the 1960s seems quaint and overly optimistic in 2016 when the world has witnessed devastating epidemics, and here in the U.S., foreign pathogens such as dengue and monkey-pox have reached our shore. The medical community must also be prepared for an outbreak triggered by a domestic pathogen as well as those of more exotic origin.

While the saying goes that no one comes to work looking to make mistakes, they do happen, and they can lead to serious adverse events and poor patient outcomes. Where humans can introduce errors into a process, machines can help ensure standardization and uniformity, and an increasing number of healthcare organizations are evaluating and purchasing automated systems that boost their risk management strategies and patient safety efforts. Automation-driven processes are free from human fatigue and error, so they can help provide consistency and accuracy and potentially lead to a reduction in patient complications, infections and deaths. More predictable outcomes are possible with automated technology, and higher throughout can be achieved.

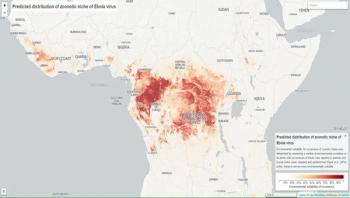

Though the West African Ebola outbreak that began in 2013 is now under control, 23 countries remain environmentally suitable for animal-to-human transmission of the Ebola virus. Only seven of these countries have experienced cases of Ebola, leaving the remaining 16 countries potentially unaware of regions of suitability, and therefore underprepared for future outbreaks.

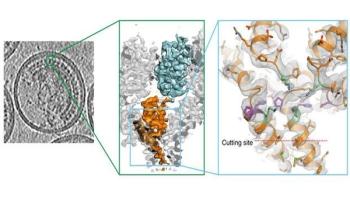

The atomic structure of an elusive cold virus linked to severe asthma and respiratory infections in children has been solved by a team of researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Purdue University. The findings are published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) and provide the foundation for future antiviral drug and vaccine development against the virus, rhinovirus C.

Besides mushrooms such as truffles or morels, also many yeast and mold fungi, as well as other filamentous fungi belong to the Ascomycota phylum. They produce metabolic products which can act as natural antibiotics to combat bacteria and other pathogens. Penicillin, one of the oldest antibiotic agents, is probably the best known example. Since then, fungi have been regarded as a promising biological source of antibiotic compounds. Researchers expect that there is also remedy for resistant pathogens among these metabolites.

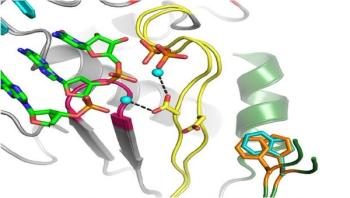

A new type of HIV drug currently being tested works in an unusual way, scientists in the Molecular Medicine Partnership Unit, a collaboration between EMBL and Heidelberg University Hospital, have found. They also discovered that when the virus became resistant to early versions of these drugs, it did not do so by blocking or preventing their effects, but rather by circumventing them. The study, published online today in Science, presents the most detailed view yet of part of the immature form of HIV.