News

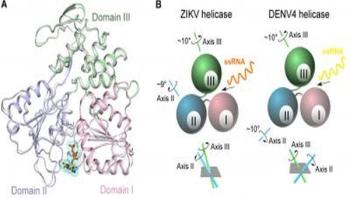

An international team led by researchers from Tianjin University and Nankai University has unraveled the puzzle of how Zika virus replicates and published their finding in Springer's journal Protein & Cell.

Pneumonia is the most prevalent infection after open-heart surgery, leading to longer hospital stays and lower odds of survival. But a new analysis of data from thousands of patients who had coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery at Michigan hospitals revealed ways people can prepare their bodies to reduce the risk of postoperative pneumonia -- a complication that occurred in 3.3 percent of patients in the observational review.

Q: I was at a conference recently and the speaker said that emergency eyewash stations are needed at all locations where chemicals are used. Can you provide more information on this?A: The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) has a standard, American National Standard for Emergency Eyewash and Shower Equipment, Z358.1-2014. This document “establishes minimum performance and use requirements for eyewash and shower equipment” for anyone whose eyes or body have been exposed to hazardous materials or chemicals. This standard is also an excellent reference for “performance and use requirements for personal wash units and drench hoses, which are considered supplemental to emergency eyewash and shower equipment.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) today issued updated guidance and information to prevent Zika virus transmission and health effects.

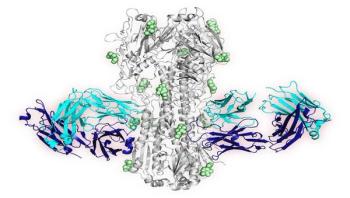

Scientists have identified three types of vaccine-induced antibodies that can neutralize diverse strains of influenza virus that infect humans. The discovery will help guide development of a universal influenza vaccine, according to investigators at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), both part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and collaborators who conducted the research. The findings appear in the July 21 online edition of Cell.

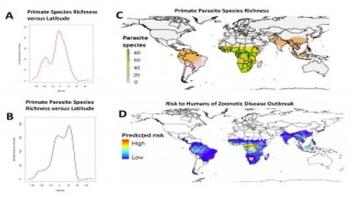

Ecologists at the University of Georgia are leading a global effort to predict where new infectious diseases are likely to emerge. In a paper published in Ecology Letters, they describe how macroecology-the study of ecological patterns and processes across broad scales of time and space-can provide valuable insights about disease.