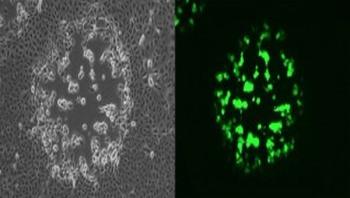

Almost all human beings are exposed to the respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, before their second birthdays. For most, the symptoms mimic those of the common cold: runny nose, coughing, sneezing, fever. But in some very young infants -- and some older adults -- the disease can be serious, causing respiratory problems that require hospitalization and increase the risk of developing asthma later in life. Even in the hospital, doctors can't do much more than offer supportive care. But, with a new study, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and colleagues have identified a subset of viral products that are responsible for eliciting a strong immune response against RSV in people who become infected. These products, called immunostimulatory defective viral genomes, or DVGs, were once thought to have no biological function. Now they are being eyed as a gateway through which the immune system could be coaxed to mount a defense to clear the body of the virus.