News

On June 7, 2015, the National IHR Focal Point of the Republic of Korea notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of 14 additional confirmed cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection, including one death.

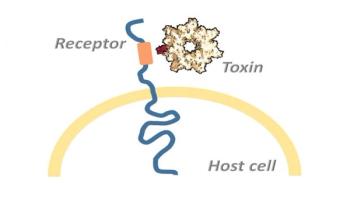

Clostridium difficile is a dangerous intestinal bacterium that can cause severe diarrhea and life-threatening intestinal infections after long-term treatment with antibiotics. The pharmacologists and toxicologists Dr. Klaus Aktories and Dr. Panagiotis Papatheodorou from the University of Freiburg have identified the molecular docking site that is responsible for the C. difficile toxin's being able to bind to its receptor on the membrane of the intestinal epithelium. This docking site functions like an elevator, transporting the toxins into the cell's interior. By binding to the surface receptor, the toxins are able to overcome the cell membrane. Once inside the cell, C. difficile exerts its full lethal effect.

On June 6, 2015, the National IHR Focal Point of the Republic of Korea notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of nine additional confirmed cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection.

Q: On occasion, I will be asked to process a device which does not have instructions for use. Sometimes, the item is not a medical device (e.g., zipper). I am told I must process the device because the surgeon requires it for a case. I usually process the device. I have just learned this is not the correct practice. How do I handle this?

An upset in the body's natural balance of gut bacteria that may lead to life-threatening bloodstream infections can be reversed by enhancing a specific immune defense response, UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers have found. In the study, published online in Nature Medicine, scientists identified how a certain transcription factor -- a protein that that turns genes on and off -- works in partnership with a naturally occurring antibiotic to kill infection-causing fungi called Candida albicans.

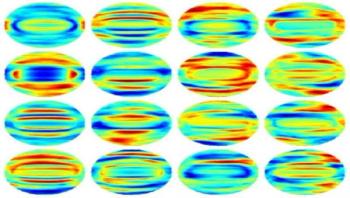

A new way of rapidly identifying bacteria, which requires a slight modification to a simple microscope, may change the way doctors approach treatment for patients who develop potentially deadly infections and may also help the food industry screen against contamination with harmful pathogens, according to researchers at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) in Daejeon, South Korea.

Between June 1 and June 4, 2015, the National IHR Focal Point for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of five additional cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection, including one death.

On June 5, 2015, the National IHR Focal Point of the Republic of Korea notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of five additional confirmed cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection, including one death.

Dr. Philip Ireland, a native Liberian, credits his survival from Ebola virus disease on the care he received from his mother, the prayers of a compassionate nurse, and the unity of a country motivated to drive Ebola from its borders. Today, he is a strong advocate for infection prevention and control measures and is training and teaching Liberia’s next generation of doctors and specialists.

Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers are a costly, adverse event. The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel estimates that U.S. healthcare systems spend $11 billion treating each year treating pressure ulcers; the cost to treat each pressure ulcer and related complications can range from $500 to $70,000. Outside of the financial cost, pressure ulcers can have a devastating effect on patients-from the risk of developing cellulitis or infection of joints and blood, to increased length of stay and higher risk of death from associated complications.