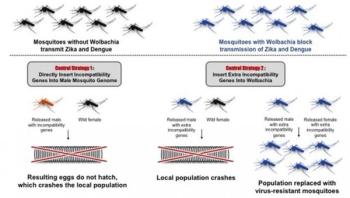

Wolbachia is the most successful parasite the world has ever known. You’ve never heard of it because it only infects bugs: millions upon millions of species of insects, spiders, centipedes and other arthropods all around the globe.

Wolbachia is the most successful parasite the world has ever known. You’ve never heard of it because it only infects bugs: millions upon millions of species of insects, spiders, centipedes and other arthropods all around the globe.

Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP) have identified a new regulator of the innate immune response--the immediate, natural immune response to foreign invaders. The study, published recently in Nature Microbiology, suggests that therapeutics that modulate the regulator--an immune checkpoint--may represent the next generation of antiviral drugs, vaccine adjuvants, cancer immunotherapies, and treatments for autoimmune disease.

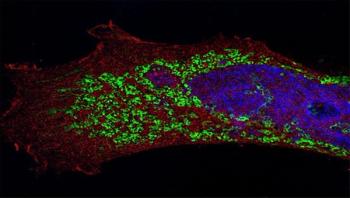

Gene transfers are particularly common in the antibiotic-resistance genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria. When mammals breed, the genome of the offspring is a combination of the parents' genomes. Bacteria, by contrast, reproduce through cell division. In theory, this means that the genomes of the offspring are copies of the parent genome. However, the process is not quite as straightforward as this due to horizontal gene transfer through which bacteria can transfer fragments of their genome to each other. As a result of this phenomenon, the genome of an individual bacterium can be a combination of genes from several different donors. Some of the genome fragments may even originate from completely different species.

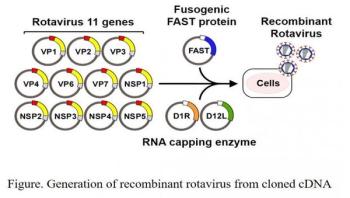

Rotaviruses are the most common cause of severe diarrhea and kill hundreds of thousands of infants a year. Although current vaccines are effective in preventing aggravation of rotaviruses, the development of more effective vaccines at lower cost is expected. Technology cannot study well how rotaviruses invade and replicate in a cell. To identify which genes are crucial for the infection of rotaviruses, scientists at the Research Institute for Microbial Diseases at Osaka University report a new plasmid-based reverse genetics system. The study can be read in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

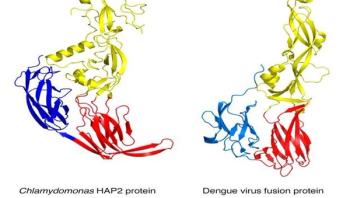

Sexual reproduction and viral infections actually have a lot in common. According to new research, both processes rely on a single protein that enables the seamless fusion of two cells, such as a sperm cell and egg cell, or the fusion of a virus with a cell membrane. The protein is widespread among viruses, single-celled protozoans, and many plants and arthropods, suggesting that the protein evolved very early in the history of life on Earth.