News

A new survey published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases suggests that many Americans don’t consider antibiotic resistance to be an important problem or fully grasp how resistance develops. A majority of survey respondents agreed that inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance (92 percent) while (70 percent) responded neutrally or disagreed with the statement that antibiotic resistance is a problem.

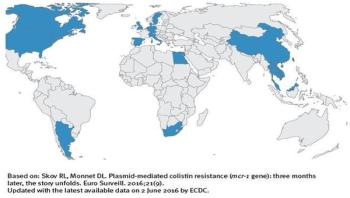

The recently recognized global distribution of the mcr-1 gene poses a substantial public health risk to the EU/EEA, asserts the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The gene is widespread in several continents and has been detected in bacteria isolated from multiple different sources such as food-producing animals, food, the environment and humans.

Viruses can't live without us -- literally. As obligate parasites, viruses need a host cell to survive and grow. Scientists are exploiting this characteristic by developing therapeutics that close off pathways necessary for viral infection, essentially stopping pathogens in their tracks. Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) and other members of the bunyavirus family may soon be added to the list of viruses denied access to a human host. Sandia National Laboratories researchers have discovered a mechanism by which RVFV hijacks the host machinery to cause infection. This mechanism offers a new approach toward developing countermeasures against this deadly virus, which in severe human infections causes fatal hepatitis with hemorrhagic fever, encephalitis and retinal vasculitis.

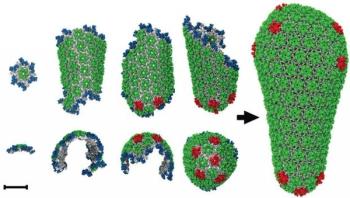

From a virus's point of view, invading our cells is a matter of survival. The virus makes a living by highjacking cellular processes to produce more of the proteins that make it up. From our point of view, the invasion can be a matter of survival too: surviving the virus. To combat viral diseases like HIV-AIDS, Ebola, and Zika, scientists need to understand the "life cycle" of the virus and design drugs to interrupt it. But seeing what virus proteins do inside living cells is extremely difficult, even with the most powerful imaging technologies. Now, University of Chicago scientists and their colleagues have developed an innovative computer model of HIV that gives real insight into how a virus "matures" and becomes infective. In doing so, it offers the prospect of help developing new anti-viral drugs and greatly extends what has been possible with computer simulations of biological systems. Their findings appeared in the May 13 edition of Nature Communications.

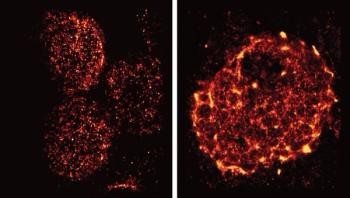

When the body is fighting an invading pathogen, white blood cells--including T cells--must respond. Now, Salk Institute researchers have imaged how vital receptors on the surface of T cells bundle together when activated. This study, the first to visualize this process in lymph nodes, could help scientists better understand how to turn up or down the immune system's activity to treat autoimmune diseases, infections or even cancer. The results were published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

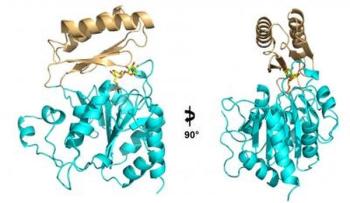

Fungal infections can be devastating to human health, killing approximately 150 people every hour, resulting in more than 1 million deaths every year, more than malaria and tuberculosis combined. Unfortunately the antifungal drug arsenal is limited, with many of the best drugs more than 50 years old. The search for new antifungals has recently alighted on a simple biological pathway, the production of trehalose, a chemical cousin to table sugar that pathogenic fungi need to survive in their human hosts. A team of Duke researchers has solved the structure of an enzyme that is required to synthesize this fungal factor.